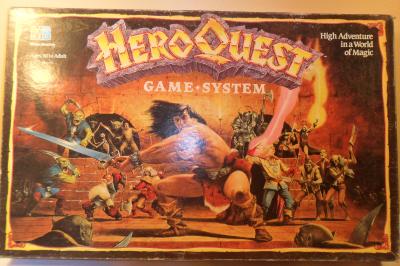

This review is about as nostalgic I can get for a game. Many of us had our first experiences with role-playing through the various editions of Dungeons and Dragons, or even White Wolf. For me, my first experience was with HeroQuest. At its heart, HeroQuest is a dungeon hack sort of game, with an actual person playing the Game Master (aka the evil Zargon), but with a little imagination it can become a full fledged RPG.

Given the need for someone to ‘run the board’, the game can support up to four players who have to figure out how to work together versus the evil Zargon, or one player controlling all the good guys, and one as the bad. What is fantastic is that you are actually playing against the GM, meaning there is the potential to lose. The actual goal of the ‘evil’ player is to kill all of the others. Have a friend with a little pent up aggression, you might not stand a chance.

An interesting aspect to start the game is that it isn’t always the same game. There are five different adventures that come with the game, and the GM has maps laid out for him in his private little book. Before you start playing, you are told the introduction paragraph which sets the stage for one of the five games. Games Workshop & Milton Bradley did an excellent thing with HeroQuest, by not only offering you new adventure modules to make your core game last even longer.

One last piece of gushing before we get to the core mechanics is that the miniatures and set design in this game are unrivaled. Even when you look at some of the pieces you get in a game like Descent or Runebound, the tiles, furniture, and monsters that come with the HeroQuest game are staggering even for today’s standards.

Okay, enough prattling about how nostalgia. To the game:

How To Play HeroQuest

Once you know why you are traversing through the dungeon, it is time to start. All of the players have a starting spot, as dictated by the GM’s evil little book, and roll two six sided dice to determine how far they can move. In front of the players is a map of a predesigned dungeon, that is different each time you try a different adventure. Each of the adventurers (Dwarf, Elf, Wizard and Barbarian) take turns moving around and anytime there is a new line of sight, the GM fills in the squares with whatever you see from doors to passage blocking rubble.

The hero may also take one other action. That action can be attacking, searching for treasure or traps, or casting spells (if they have any at the time). Combat is an easy roll of two different kinds of dice. Skull dice are rolled by the attacker, and shield dice by the defender. Depending on your attack stat, you roll that many number of dice, and however many skulls rolled over the amount of shields rolled is the amount of damage. For the most part, you’ll find that your barbarian and dwarf are going to do the most melee combat, while the elf and wizard remain your ranged figures, but the addition of different special artifacts and bought equipment (more on that in a moment) can change that from game to game.

If the wizard or elf decide to use their spells, they take their chosen spell cards and read from the back. The game is very meticulous about explaining what each spell does, so there is little room for confusing interpretation. A good GM might add in some flavor details, but otherwise the spells do what they do and little else.

When a character searches, the GM goes to his little book and dictates whether or not they find anything that is a key object, necessary for the quest, or a special optional object. If not, the players pull from the treasure deck that might have any number of fantastic golden goodies, or another monster for them to have to defeat.

This play continues until either the heroes are all dead, or the heroes have found the treasure/saved the princess/killed the bad guy and gotten out. That is a key component that I remember causing my party of friends no end of trouble. The game makes sure that, even if you find the treasure, you actually escape from the dungeon. This plays a factor only if you are going to be keeping your characters, buying treasure with your found loot, and using them again for the next game.

HeroQuest Strategy

There are a few strategies that come into play with HeroQuest, but so much of them has a meta-game feel that I’m loathe to discuss them too deeply.

For example, if the last good player goes and searches for treasure and finds a monster, the monster will get a free surprise attack on them, and then the GM gets to go and get another attack. Two attacks in a row is quite a boon for the side of evil, so it is best to avoid that.

Also, whenever you kill a wandering monster, it goes right back into the treasure deck, so the more you search and hunt for loot, the more likely it is that you will run into monsters more and more, until the dungeon is overrun.

Writing this review, and researching all of the nuances of the game that I had forgotten has made me completely and utterly wanting to find a copy and play it again. If that isn’t a testament to this game, then nothing is. There is a sequel in Advanced HeroQuest, that I heard was close, but missed some of the mark. Then there was Warhammer Quest which came exceptionally close, but can get a bit tedious in its random dungeon generation. HeroQuest isn’t a game for the experienced roleplayer to have a fulfilling narrative experience, but it is a great way to kill an afternoon and introduce someone into roleplaying.

The game offers you a great selection of dungeons, and even blank sheets for a creative GM to make their own world up and continue your heroes adventure from beginning to end. As with any good story based game, it will only be as fantastic as the players and storyteller make it. If you have a little one that you want to introduce RPGs to, but without all the weight that Dungeons and Dragons or a D20 possesses, then grab HeroQuest and know you will not be disappointed.